Before the Pyramids: Neolithic Newgrange

- ptcrawford

- Jan 8, 2023

- 6 min read

It was this writer's great good fortune to enter the Neolithic passage tomb of Newgrange and some of its surrounding environs and accompanying museum.

Along with nearby Knowth, Dowth and other mounds, standing stones, henges and prehistoric enclosures, Newgrange makes up the Brú na Bóinne - 'Palace of the Boyne' - UNESCO World Heritage site in Co. Meath (one of only three on the entire island of Ireland).

Constructed in c.3200BC, the passage tomb of Newgrange is older than both Stonehenge and the Pyramids. There is no firm consensus about what the site was used for, but it appears more ritual or religious than anything else, particularly with the presence of three alcoves at the head of the passage.

Newgrange was not always the striking site it is now or was upon its completion. Perhaps by the Late Neolithic period - c. 2000BC, the site had fallen into decay with nature starting to cover over the site. That said, it must have retained some ritual significance as seen with deposits of various types through the Iron Age, including the Roman deposits discussed below, and even some deposits that can only have some from the medieval period, such as the remains of rabbits, which only arrived in Ireland in the 13th century.

Despite any such continuation of local reverence, it is possible that the passage tomb had been almost completely subsumed by the local landscape by the medieval period with cattle grazing on top of the mound. That same field was also subsumed by the lands of the Cistercian Abbey of Mellifont and later the lands of the earls of Drogheda.

The passage tomb was not revealed again until Charles Campbell, who held a 99 year lease on the land from the Countess of Drogheda, ordered workmen to dig into the mound to retrieve some stone. Recognising that he had found something more than just a pile of stones, Campbell allowed a parade of antiquarians to investigate the site, many of whom refused to believe that it had been built by local prehistoric peoples. This led to suggestions of Egyptian, Indian or Phoenician involvement in its construction.

Even with this recognition of the importance of the site, it was left largely open until the late 19th century, leading to vandalism and theft. Conservation efforts began in 1890, but the definitive (although not without some controversy over the restoration) archaeological survey by Professor Michael O'Kelly did not being until 1962.

Squeezing through the 19 metre narrow passage with 200,000 tonnes of graduated stone and kerbstones above and around, trying not to smash your head against the ceiling or rub too much against the sides, you do not get the impression of going up-hill. However, by the time you enter the main tomb with its three alcoves and striking layered ceiling, complete with a 40 tonne capstone, your feet are now level with the top of the entrance. While initially this just seems like a way to place the alcove tombs in a ceremonially higher position, it will be seen below that there was much more to this elevation.

Walking around the acre-sized mound (85 metres wide, 13.5 metres high), we were struck by not only the 97 enormous kerbstones ringing the mound and the satellite tomb, which turned out to be a 'folly' tomb made up of stone culled from Newgrange itself in a form of 19th century antiquarian vandalism, but also the large semi-circular bank surrounding half of the mound.

Perhaps showing a lack of archaeological knowledge, it was speculated in my group that it might have been part of an attempt to make the mound appear in the same spiral shape prevalent around Newgrange. We found that it was instead comprised of cairn materials which had slipped from the mound, essentially burying the kerbstones. During the restoration of the Newgrange site, it was decided to retain the cairn slip semi-circular mound, only uncovering the kerbstones which it had obscured from view.

The survival of such a seemingly rudimentary structure which used no form of cement (gaps between the major stones were filled in with other stone) is in itself astounding but even more so is that fact that the central passage tomb has remained completely water tight over the millennia since the capstone was put in place.

Not only are many of the stones used to construct Newgrange of a vast size and number, they are also not exactly from the nearby hills. The quartz and granite used at the site came from up to 70 miles away in Wicklow and Dundalk. And this was almost certainly at a time before the advent of the wheel in Ireland and domesticated beasts of burden (and most probably all of Europe too), so the likelihood is that the stones were floated along the Boyne, rolled on felled trees and muscled into position through ramps and good, old-fashioned manpower.

It is not only the architectural prowess which is so eye-opening, but also the artistic techniques of the Stone Age farmers who built this monument. Many of the stones in and around Newgrange are engraved with various Neolithic patterns. Indeed, the Boyne Valley as a whole contains a significant proportion of Europe's Neolithic art.

One of the more prominent art techniques around Newgrange and most prominently displayed on the vast Entrance Stone are the triskele-like patterns. Whilst this type of triskele is seemingly unique to Newgrange, the triskele itself was widely used.

There has been plenty of speculation as to what this preponderance of triskele spirals could mean beyond decoration - are they some for of map? The layout of the stars? A language or even drug-induced hallucinations?

Newgrange and the Winter Solstice

If the art and architecture were not awe-inspiring enough, Newgrange had one more astronomical secret for those charged with unearthing it. The onsite museum (as well as providing plenty of opportunity to buy plenty of Irish-theme merchandise and extremely appetising food) tells the story of how Professor Michael O'Kelly, principal excavating archaeologist from 1962-1975, came to uncover one of Newgrange's hidden mysteries and quite possibly one of its main reasons for being where it is - its alignment with the sun of the winter solstice.

Professor O'Kelly and his team had heard of local traditions surrounding the solstice and even Newgrange's use of it for ritual purposes, but it was not until the winter of 1967 that the professor saw what was in all likelihood the reason for the elevation of the alcove tombs to the level of the entrance…

"At 8:58 hours, the first pencil of direct sunlight shone through the roof-box and along the passage to reach across the tomb chamber floor as far as the front edge of the basin stone in the end recess." Professor Michael J. O'Kelly, 21st December 1969

It turns out that the whole Newgrange mound was oriented with the winter solstice in mind so that the light of the sun on the shortest day - 21 December - would shine through the passage into the alcove at the head of the tomb. The exact reasoning for this is unknown - general sun worship, celebrating the turning of the season, allowing the cremated remains in the passage tomb to 'see' the sun or partake in solstice?

Getting to see this annual event has become the focus of a lottery in the Boyne Valley museum, with twenty people chosen to stand in the passage tomb at the appointed time to be greeted by the approaching beam of light (weather permitting) - over 32,000 attempted to win that privilege. While inside the passage tomb, non-solstice visitors are given a taster of what they beam of light might look like creeping through the otherwise perennial darkness.

Such an astronomical alignment encouraged similar investigations at Knowth and Dowth, with the latter having a similar winter solstice alignment as Newgrange and the former being aligned with the spring and autumn equinoxes.

Clearly, these Stone Age farmers who had no domesticated animals or the wheel were well-advanced in knowledge of the astronomical events of their world.

Roman Material at Newgrange

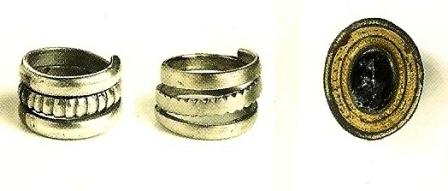

As this is a classical blog, it would be remiss of me to not mention the finds of Roman material at the site. A significant collection of rings, brooches, torcs and gold, silver and base coins were found near the entrance and at the larger of the stone circle surrounding Newgrange.

The coins depict emperors ranging from the late first century to the late fourth century. A catalogue of these coins was collated by R.A.G. Carson of the British Museum for the Royal Irish Academy in 1977, running to some 25 coins including two now lost from the 1842 finds recorded by Conyngham (1844).

Domitian (81-96)

Geta (209-211)

Gallienus (253-268)

Postumus (Gallic emperor, 260-269)

Probus (276-282)

Maximian (286-305, 306-308, 310)

Constantine I (306-337)

Constantine II (337-340)

Magnentius (350-353)

Valentinian I (364-375)

Gratian (367-383)

Theodosius I (379-395)

Arcadius (383-408)

Of all the 20 coins from which a mint mark can be ascertained, the majority (11) come from the imperial mint at Trier, now in Germany. The three earliest coins of Domitian were all made in Rome, along with another of Probus. The remaining coins came from the mints at Cologne, Amiens, Milan and London.

In the very least this demonstrates some interaction between the Roman and Irish worlds and that Roman items were considered valuable enough to dedication to whatever rituals or gods were held sacred on the site of Newgrange during or after the fourth century.

Further Reading

https://voicesfromthedawn.com/newgrange/

https://www.boynevalleytours.com/newgrange.htm

http://irisharchaeology.ie/2013/04/roman-coins-from-newgrange/

http://irisharchaeology.ie/2011/11/roman-contacts-with-ireland/

http://www.miotas.org/article.cfm?id=Newgrange

https://web.archive.org/web/20170531214317/http://www.mythicalireland.com/ancientsites/newgrange/illumination.php

Bateson, D. 'Roman material from Ireland: a reconsideration', in PIRA 73 (1973) 21-97

Carson, R.A.G. and O'Kelly, Claire 'A Catalogue of the Roman Coins from Newgrange, Co. Meath and Notes on the Coins and Related Finds,' PIRA 77 (1977) 35-55

Conyngham, A. 'Description of some gold ornaments recently found in Ireland,' Archalogia 30 (1844) 137

O'Kelly, M.J. Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend. London (1982)

For more photos, see https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.2184276221842202&type=3

This piece was previous posted on the CANI website and is reposted here with permission

![“What a [Herculean] Manoeuvre!”: Inventing the Bear Hug](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/a3d50b_8b9ad5c763e042409eb39fc07801a1a2~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_800,h_1339,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/a3d50b_8b9ad5c763e042409eb39fc07801a1a2~mv2.jpg)

Comments