Censeris Caesar: Yet Another British Imperial Pretender or a Mixed-up ‘Carausius II’?

- ptcrawford

- Jun 29, 2025

- 8 min read

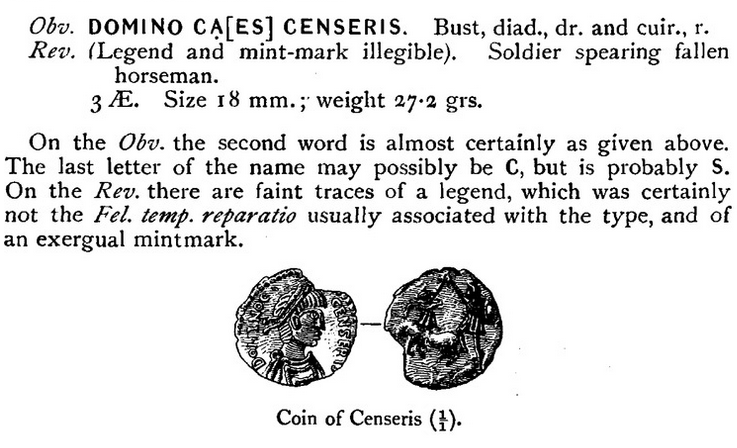

In all the numismatic discussions of ‘Carausius II’, who he might have been and when he might have attempted to rule, there is another potential individual who is somewhat overlooked. Found amongst a group of about 400 coins at Richborough was an issue with the obverse legend of DOMINO CΛ.. (ENSERIS, taken to mean Dominus Caesar Censeris/Genseris.

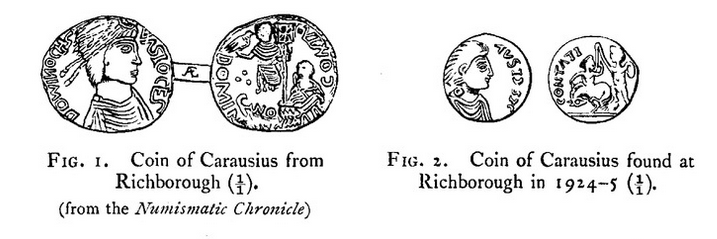

This would seem to posit another man of imperial position in Britain in a similar period as ‘Carausius II’, with the coins of both men sharing an “intimate connexion” (Pearce (1928), 364; cf. Salisbury (1926), 312 figs.1-2).

The main basis of that ‘connexion’ is type. Looking at the ‘Censeris/Genseris’ coin, its reverse legend is largely illegible, but while Pearce (1928), 364 suggests that what can be seen is not the letters of FEL TEMP REPARATIO, the ‘Censeris/Genseris’ issue does host a ‘Fallen Horseman’. This means that it is similarly based on the ‘Fallen Horseman’ FEL TEMP REPARATIO type as the vast majority of the ‘Carausius II’ coins.

This also means that chronologically placing ‘Censeris/Genseris’ is beset by the same issues as with ‘Carausius II’ and indeed follows the same development – initially he was seen as an early fifth century usurper from the time of Constantine III, only to later be moved to the 350s, during the reign of Constantius II. And “in the light of studies of the internal chronology of the FEL TEMP REPARATIO coinage, it is possible to isolate the production of the Carausius and Censeris copies to the years 354-8” (Casey (1994), 160).

Without going into too much repetitive detail on the coin’s detail, like ‘Carausius II’, ‘Censeris/Genseris’ is inscribed with the titles of ‘Lord’ and ‘Caesar’. Again DOMINO is a peculiar, and indeed, poor Latin declension, likely highlighting the local origin of the coins.

This chronological, geographic and numismatic similarity also sees all the same political questions asked about ‘Censeris/Genseris’ – was he a local secessionist like the first Carausius? Was he a rebel against Magnentius through loyalty to Constantius II? Or a local usurper orchestrated by the regime of Constantius?

All of these questions face the same arguments – dating of the coin types removing Magnentius as a direct factor, Constantius unlikely to have signed off on a local usurpation etc. – and the same lack of definitive answer about the identity and even existence of ‘Censeris/Genseris’…

However, there is one major avenue of difference to contend with in dealing with ‘Censeris/Genseris’ in comparison with ‘Carausius II’: what appears to be the rather obviously different name. The choice to receive the ‘(’ as either a ‘C’ or a ‘G’, rendering it ‘Censeris’ or ‘Genseris’ could have significant ethnic consequences for the depiction of this man.

Following the ‘C’ route, Anscombe (1927-1928), 9 contended that the legend on the ‘Censeris’ coin found at Richborough read DOMINO CENS-ΛVRIO CES “and that it should be regarded as dedicatory, and be expanded and normalized as follows: DOMINO CENSORIO CAESARI.”

Despite seeming to be a good Roman name, ‘Censorius’ appears a little less frequently amongst Roman sources than might be expected. Under the Roman Republic, the similar ‘Censorinus’ was a more popular name, being a cognomen for the plebian gens Marcia. This was a family whose members that held all the major offices of state, including the censorship, where their name came from. There were also some Censorini who acted as moneyers, immortalising their name on coins. Several of them were also friends and enemies of many of the prominent men in the Fall of the Republic.

During the reign of Claudius II (268-270), there was reputedly a usurper in Italy called Censorinus, who only lasted a few days before being executed by his soldiers (SHA Tyranni Triginta 33). While this Censorinus seemingly being a complete fabrication by the writer(s) of the Historia Augusta (Barnes (1978), 69; Rohrbacher (2016), 118; Syme (1968), 157) might seem to nullify him as an example, the fact that the fourth century Historia Augusta uses that name in a fabrication might hint at some popularity for that name in Late Antiquity.

As for ‘Censorius’ specifically, the most prominent late antique examples are both from the fifth century. The comes Censorius playing a prominent role in Romano-Suebic relations in Spain during the 430s, which is recorded in the Chronicle of Hydatius, while the Life of St Germanus, written by Constantius of Lyon, was addressed to Censorius, bishop of Auxerre.

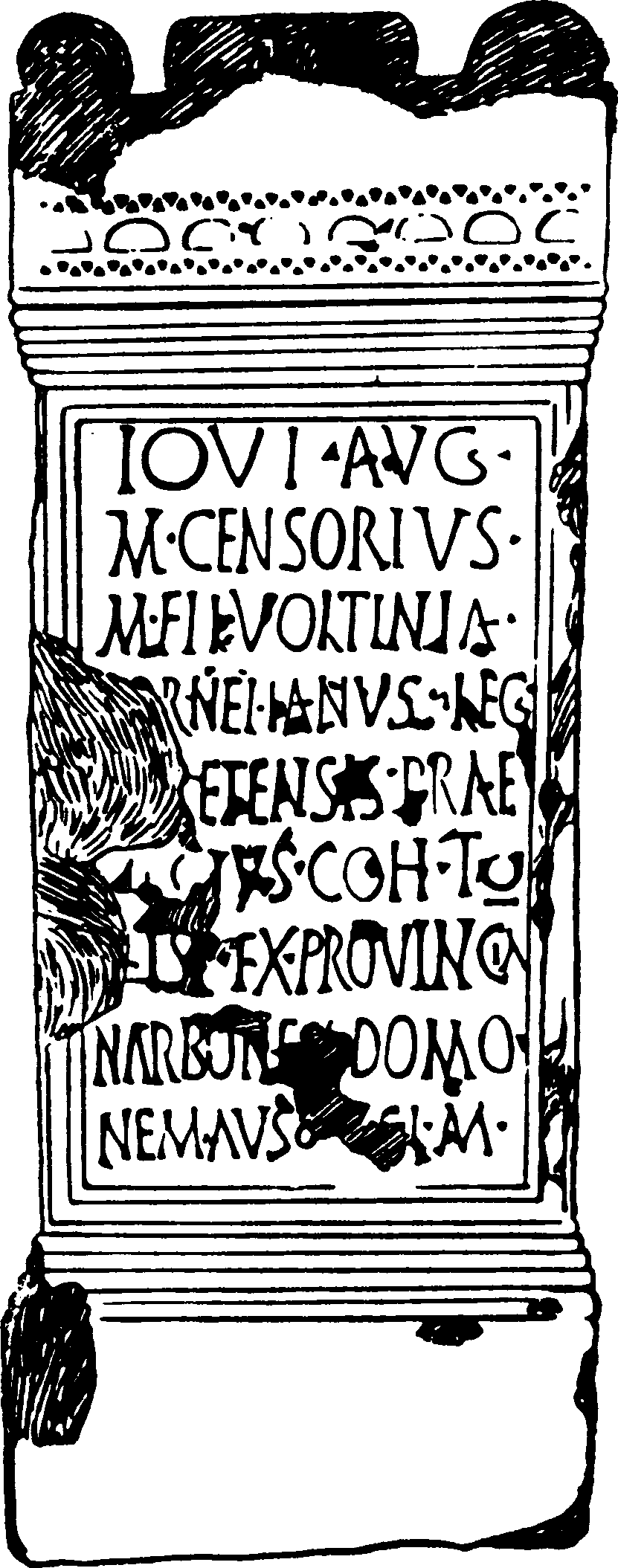

There are also versions of the name in Romano-British inscriptions (CIL VII.1336, 289 and 291), and while it is not dateable, there is an altar of Marcus Censorius Cornelianus, who, while a native of Gallia Narbonensis and a centurion of the Legio X Fretensis, found himself in Britain, specifically Uxellodunum, near what is now Maryport in Cumbria. This would suggest service along Hadrian’s Wall, possibly as praepositus of the I Hispanorum cohort (RIB 814; CIL VII.371). There are other similar names recorded at Chichester, Caerleon and elsewhere (Anscombe (1927-1928), 10).

Anscombe (1927-1928), 10 commented that of all these Late Roman ‘Censorius’ and similar names, “not one indicates an official of high status… as is demanded for "Censaurius Cesar"”. However, this is not the empire of the first or second century – if the military crisis of the third century had revealed anything, it was that a man of any background could see himself elevated to empire. So, the idea that there are few or no ‘Censorius’ of high rank known of in Late Antiquity is really of no consequence. The only benefit to be gleaned from this collection of men and women named ‘Censorius’ or similar is that it shows that the name was in circulation in western Europe and specifically Britain during the period that ‘Censaurius Cesar’ may have attained some imperial power.

Anscombe (1927-1928) also goes to significant etymological, historiographical and even mythological lengths to connect his ‘Censaurius Cesar’ to characters who appear in various historically based legends, such as Arthur and Beowulf. Not only does this stretch the bonds of credibility, it would also seem to be based on the initial chronology of Evans (1887), pre-eminent at the time of Anscombe’s writing, that deposited ‘Censaurius Cesar’ in the first decade of the fifth century, rather than the 350s.

But what if the ‘(’ was meant to be a ‘G’, and the man on the Richborough coin was actually ‘Genseris’? Such a name looks decidedly Germanic in origin, with the most famous, similar name would be Geiseric, king of the Vandals (428-477), a name which is also recorded as either ‘Gaiseric’ or ‘Genseric’. The change in this name from something like the more Germanic ‘Gaisaris’ to ‘Genseris’ could be due to Roman pronunciation and then spelling of the Germanic original or possibly an inscribing error (Stevens (1956), 348-349).

But why would a potential Roman usurper have a German name in mid-fourth century Britain? It might have seemed to make more sense when this whole episode of ‘Carausius II’ and ‘Genseris’ was thought to have taken place in the first decade of the fifth century when Germanic tribes were menacing Roman territory in significant numbers and settling in parts of Britain with increasing frequency. The redating of this episode to the mid-350s lessens this impact somewhat, but then there were Vandals and Burgundians settled in Briain under the emperor Probus in c.277/278 (Zosimus I.68.3).

There is another linguistic suggestion for the origin of ‘Censeris/Genseris.’ Could it be that local dialects, scribal errors and political expedience have corrupted ‘Censeris/Genseris’ into something like Carausius? (Stevens (1956) 348-349) As was seen in the previous ‘Carausius II’ piece, given the number of mistakes made with it, ‘Carausius’ seems to have been a difficult name to inscribe – CARAVƧIO, (ARVƧI etc. (so seemingly was ‘Constantius’: CONTA, (OHTATI, (ONSTAN, (ONSTATI, CONXTA[NTI]NO)

Could it be that the original ‘Carausius’ was corrupted to ‘Ceris’, then to ‘Censeris/Genseris’ (Evans (1887), 197 n.9) and then possibly back to ‘Carausius’ when the corrupted forms did not look ‘Roman’ enough for someone claiming an imperial position?

This would suggest that ‘Carausius II’ and ‘Censeris/Genseris’ were in fact the same person. On top of some potential linguistic connection, their coins sharing the same base type, influences and time period. The smaller number of so far discovered ‘Ceneris/Genseris’ coins in comparison to ‘Carausius II’ could hint at a single usurper changing his name from a Latin/Germanic name to a more obviously Romano-British imperial name.

However, this comparative paucity of ‘Censeris/Genseris’ coins might actually work to detach him from ‘Carausius II’; his lower numismatic output possibly suggesting that he was a shorter-lived predecessor or successor of ‘Carausius II’.

One could possibly invoke the numismatics of another regional Roman revolt that took place over 250 years later – that of the Heraclii in Africa. It was initially focused on Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Carthage, only for his son, also Heraclius, to take the active role in claiming the imperial throne for himself in 608-610. The Elder then died not long after hearing news of his son’s accession, reducing the number of coins he appears on.

Could we be seeing something similar here with ‘Censeris/Genseris’ being a colleague, even relative of ‘Carausius II’ who was sidelined for some reason? Early death? Defeat by local forces? Or perhaps he was raised to power by ‘Carausius II’ later as a colleague/successor, only for the regime to collapse before many coins could be minted of him?

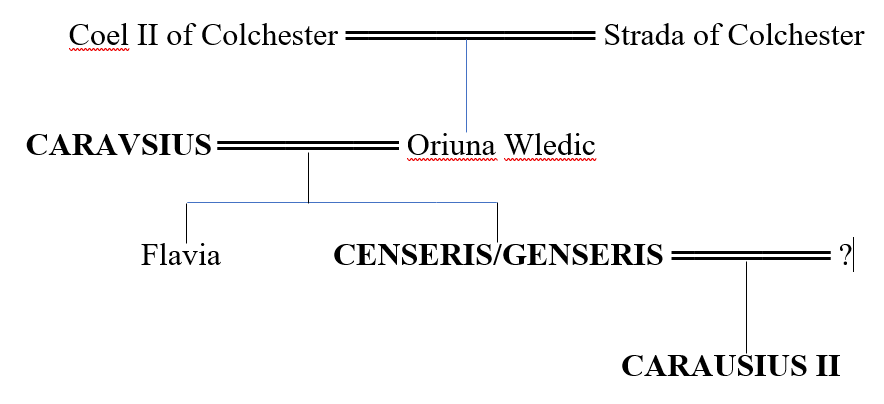

This idea of a familial connection between ‘Censeris/Genseris’ and ‘Carausius II’ permeates interpretations of British folklore, particularly with the attempts to connect this second Carausius with the first British imperial ruler of that name.

In chronological terms, such a direct connection between Carausius and ‘Carausius II’ is not out of the question. With Carausius having been killed in 293, any son he fathered would had to have been at least 61 years old by 354: not old enough to be ruled out, and also easily old enough to have a son…

Some mythological interpretations saw one of the sons of Carausius and Oriuna Wledic being named ‘Genseris’ – do we have the makings of a family tree?

As fun as it may be to draw family trees, this is entirely fanciful stuff (the Constantinian dynasty is frequently shoehorned into this Carausian/Oriunan mess) and as we saw last time with ‘Carausius II’, the entire existence of a woman named ‘Oriuna’ being the wife of Carausius stems from a numismatic misinterpretation.

Furthermore, all of this speculation about a Latin ‘Censeris’, Germanic ‘Genseris’, a garbled ‘Carausius’ or a father/son succession is just that – speculation; as is any attempt to posit a role for ‘Censeris/Genseris’ in the political machinations of Constantius II and Magnentius.

Indeed, the redating of their coins to 354-358, and the silence of the sources, particularly Ammianus, not only detach ‘Carausius II’ and ‘Censeris/Genseris’ from the events of Magnentius’ usurpation, they are as damaging to the actual existence of ‘Censeris/Genseris’ as they are ‘Carausius II’.

75 years ago, Stevens (1956), 349 suggested that the whole story of ‘Censeris/Genseris’ (and by extension ‘Carausius II’) was still “more for the historical novelist than for the historian”, but with the hope that future research would expand upon the historical speculation of such novels into something akin to proper history. Unfortunately, this has not been the case. While there has been some limited growth in the supposed reach of ‘Carausius II’ with the discovery of more of his coins, ‘Censeris/Genseris’ remains a character as shrouded in mystery and doubt as he was in the 1950s.

Bibliography

Anscombe, A. ‘The Richborough coin inscribed DOMINO CENSAVRIO CES,’ BNJ2 9 (1927-1928) 1-23

Barnes, T.D. The Sources of the Historia Augusta. Brussels (1978)

Casey, P.J. Carausius and Allectus: The British Usurpers. London (1994)

Evans, A.J. ‘On a coin of a second Carausius, Caesar in Britain in the fifth century’, NC 7 (1887) 191-219

Kennedy, J. A Dissertation Upon Oriuna, Said to be the Empress, or Queen of Emngland, the Supposed Wife of Carausius, Monarch and Emperor of Britain. London (1751)

Pearce, J.W.E. ‘A new coin from Richborough,’ Ant. J. 8 (1928) 364-365

Rohrbacher, D. The Play of Allusion in the Historia Augusta. Madison (2016)

Salisbury, F.S. ‘A new coin of Carausius II,’ Ant. J. 6 (1926) 312-313

Stevens, C.E. ‘Some thoughts on “second Carausius”’, NC5 16 (1956) 345-349

Stukeley, W. ‘Oriuna, wife of Carausius, Emperor of Britain,’ Palaeographia Britannica: Or, Discourses on Antiquities in Britain. Number III. London (1752)

Sutherland, C.H.V. ‘Carusius II, “Censeris”, and the barbarous Fel. Temp. Reparatio overstrikes’, NC5 5 (1945) 125-133

Syme, R. Ammianus and the Historia Augusta. Oxford (1968)

Comments